"FUCK HATE" - Kurt's testimony at the

"Earth Rose" Obscenity Trial, 1968

IN THE MUNICIPAL COURT, SANTA MONICA JUDICIAL DISTRICT

COUNTY OF LOS ANGELES, STATE OF CALIFORNIA

DIVISION NO. 2 HON. HECTOR P. BAIDA, JUDGE

THE PEOPLE OF THE STATE OF CALIFORNIA, )

Plaintiff, ) No. M 37056

) VIOL. SEC. 311.Z.

) PENAL CODE), A

) MISDEMEANOR

vs.

STEVEN ALLAN RICHMOND, Defendant. )

REPORTER'S PARTIAL TRANSCRIPT OF PROCEEDINGS

FRIDAY, FEBRUARY 16, 1968

APPEARANCES:

For the Plaintiff:

MRS. CHRISTINA J. NEW, Assistant City Attorney

For the Defendant:

STANLEY FLEISHMAN, ESQ., By:

Robert Carter McDaniel

1680 North Vine Street, Suite 700,

Hollywood, California.

PASCAL J. COLLETTI, C.S.R. Reporter

THE COURT: All right. Are we ready to proceed?

MR. McDANIEL: Yes, your Honor. The defendant will call Dr. Kurt Von Meier to the stand.

KURT Von MEIER,

called as a witness by and on behalf of the Defendant, having first been duly sworn, was examined and testified as follows:

THE CLERK: State your name, please‑

THE WITNESS: My name is Kurt Von Meier.

THE CLERK How do you spell that:

THE WITNESS: K-U-R-T V-o-n-M-e-i-e-r,

DIRECT EXAMINATION

BY MR. McDANIEL:

Q--Dr. Von Meier, will you please state your occupation to the Court.

A--I am an assistant professor at UCLA.

Q--Please state for the record, if you will, the background of your educational experience, sir.

A--My Bachelor of Arts Degree from the University of California at Berkely, one year of graduate work. at the University of Madrid in Spain. My Master fine Arts Degree from Princeton University.

I have one semester of special studies at Stanford University and my Ph.D. from Princeton University.

Q--In what field was the Ph.D.?

A--In the fine arts.

Q--You also have a background in the field of archeology; is that correct?

A--Art and archeology and the fine arts including music and literature.

Q--Have you taken a large number of courses on the graduate level as well as undergraduate level of the literary arts as well a the plastic arts?

A--Yes.

Q--Will you please state some of the places where you have had occasion to teach academic subjects at the various universities.

A--Yes. I have taught the history of art and cultural history at Princeton University; also University of Auckland in New Zealand for three years and at UCLA, this is my third year of teaching at UCLA.

Q--Now, have you had occasion to become involved in areas known as intermedia studies?

A--Yes. This has been a particular concern of mine as a writer for the last two years, approximately. I have been involved not only in production of intermedia happenings, as it is sometimes called, theatrical productions is more formal term, but also I have written as a critic and primarily as a historian.

Q--Could you Please explain to the Court essentially what the dynamics of the intermedia studies are.

A--I think it is perhaps best understood in the prehistorical content.

In the Twentieth Century, the theater has been used as a basis for incorporating many other art forms so that painting and sculpture, although existing separately, are brought together in terms of a total environment.

This is often done with motion pictures and with live performances of rock bands, for instance or somewhat more formalized concert performances.

Now, this is tactile sculpture decoration as might call it in the earlier sense or architecturally made a part of the sculpture and architecture at the same time, the idea being simply to bring together all the senses for total sensorium in one particular experience.

Q--In that line, have you had occasion to work with the printed word, poetry and other aspects of the printed word as well as with the paintings and sculptures?

A--Yes, certainly, and in fact, the printed word as read and spoken forms a very important historical prototype for the happening for the total environment.

Actually, in the forties already there were occasions where poetry would be read to jazz. So, here you have a combination of literature or the medium of poetry and music. This has developed into many poetry readings and often poems will be recited along with visual imagery, slides, not necessarily connected but more aesthetically connected than logically connected.

Q--Have you had occasion to make serious studies of the concept of graphics, as I use the word here, meaning the organization of both figurative drawing type material and the printed word into pamphlets, magazines and so forth?

A--Yes. This is part of my personal concern.

While I was serving in the United States Navy, this was during the Korean War, I was involved in printing, lithography and photography. In that capacity I happened to deal every day with the printing of maps and charts and things that are not necessarily works of art in our common sense, but my every day concern with this led me to a historical interest before I actually started academic study of the history of art, and I found to my fascination that some of the same problems in graphic expression of their prototypes as far back as the the 16th Century, the development of printing in Europe after Gutenberg, the development of wood block printing, for instance, or even in the far Eastern culture with the Japanese--well-known prints of the Japanese in the Nineteenth Century, particularly.

Perhaps I just didn't make the point.

I feel that this expression is specifically concerned with the printed word, but also with the graphic representation more or less closely associated with the content of the printed word itself. It is something more integral in terms of the artistic concepts than seiplly an illustrated book, although that would be in the same line.

Q--Could you please give us a brief outline of some of the materials that you have had published yourself?

A--Yes. I am the regular correspondent for Art International art magazine, which is published in Switzerland.

It is just as the title suggests, an international art magazine. It is concerned with art criticism of the contemporary events and some historical perspective.

I have written frequently for Artforum which is probably the most widely distributed art magazine in America, together with Art News.

I have written occasional articles for newspapers and other publications, for ArtsCanada, for Art in Australia and a series of other magazines concerned with literature and the fine arts generally.

I am currently at work on a history of popular music and its relation to popular culture.

Q--Did you do a study at one time and give speeches based on this study of the concepts of violence as it applies to art?

A--Yes. As a matter of fact, I am just waiting in the mail for a copy, an advance copy of an article I wrote late last year which is scheduled to appear in ArtsCanada magazine on that specific problem of violence and the fine arts.

Q--Is that the article I have in my hand here entitled "Violence, Art and the American Way"?

A--That's right.

Q--Now, have you had occasion to make studies of the use of sexual imagery as well as the use of violence imagery in terms of writing?

A--Yes. I think for any cultural historian the topic of sexuality is a very important one and one that goes all the way back to more more academic or logical interest. I mean, certainly, our understanding of the ancient Classical Greek civilization is dependent upon certain imagery or on the problem of sexuality and this, I think, goes all the way through, certainly from the renaissance on.

Q--Now, have you had occasion to read and study the document that is being charged here in court, the "Earth Rose"?

A--Yes, indeed I have.

As a matter of fact, when this was first published. I don't recall the actual date, but this was at least a year ago, I incorporated that document as part of the subject matter in a lecture at UCLA on cultural history.

Q--Now, with you experience both as a writer and as a academician, have you come to a conclusion in your own mind with regard to the question of whether this publication is or is not obscene?

A--Yes, I have.

Q--And what is your conclusion with regard to that question?

A--Well, that there is absolutely no question about it; it is not obscene.

Q--Now, breaking that down a bit, are you familiar to a degree with the legal concept of obscenity?

A--Certainly not as an expert, but yet as a layman, I would say yes.

Q--Now, with regard to the question which I will next put to you, I will ask you does this publication, the "Earth Rose," go substantially beyond customary limits of candor in the nation today in terms of the description of the sexual activity?

A--No.

Q--Are there other publications which you have read which you know to be available which are more graphic in their depiction of the sexual activity than anything in the "Earth Rose" here?

A--Certainly, yes.

Q--Now, the next question I will ask you is this:

In your opinion as an expert in this field, is this work, the "Earth Rose," utterly without redeeming social importance?

A--No. It is not utterly without redeeming social importance.

On the contrary, it has a great deal of social redeeming importance. Well, whether it redeems it is one problem. I think so, because otherwise, I wouldn't have used it as a subject matter quite of a quite serious lecture at UCLA.

That was the whole point of using it as focal point for a commentary upon violence and upon a great number of subjects that although they might not be superficially appealing to our sensibilities, they are nevertheless terribly important, terribly relevant to what artists are expressing today and what is going on in the world today.

MR. McDANIEL: Now, may I approach the witness for a moment your honor?

THE COURT: Yes, very well.

BY MR. McDANIEL:

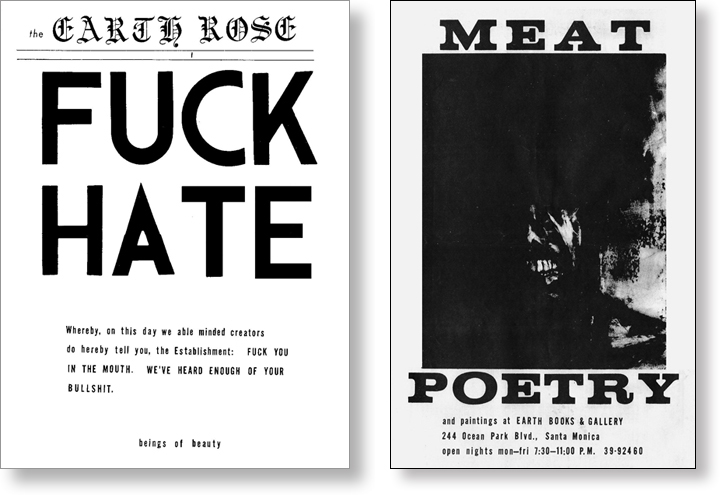

Q--I show you a copy of the document that is before the Court today, and ask you to look it over and before we talk about any of the particular writings in there, I would like your to look it over and make a statement, if you will, with regard to whether or not the use of graphics here, that is, the organization of the large printed "FUCK HATE" on the cover, the painting in the middle and so forth, finds literary precedence in your studies of the background of literature.

(The witness examined the document.)

THE WITNESS: Yes. I would be almost hard put here to describe in detail the history of this, but let me suggest that it a very long history and a very rich one.

Earlier I had occasion to mention two instances outside our own immediate context, if it is not beside the point, let me suggest that from the inception of printing around Southern Germany you find this concern with the graphic disposition of type on a page so that I think you can make a very serious case for the whole field of typography as incorporating necessarily some aesthetic concern with the way that the blacks and whites work almost abstractly, quite apart for what they happen to say, what those particular words say.

The fact that these letters are this high and the fact that they incorporate this area, you know, and make this kind of visual statement is, I think, an important aspect, not the only important aspect, certainly, but this has a valid aesthetic approach to the printed word. This goes all the way through up to the Twentieth Century and the revival of typography in the Renaissance we see typography created such as Bodoni and the very design of the type itself, for instance.

Q--Now, with regard to the "Earth Rose" itself, does it graphically--out of the use of typography and the painting and so forth--the spacing of the materials, create just by that itself without looking at the content, some of the elements that would make it a legitimate work of art?

A--Yes. This is one special way in which I have referred to it, and I think it demands to be considered.

I see here curiously enough that the title, the "Earth Rose," is in fact, in just that kind of old Fractour type. So, I mean, there is a specific point of reference but in the incorporation of photographs, of paintings and associates with the type, it carries on this very old tradition in its concern with elements of sexuality, particularly not violent so much here as I discussed in the article, but sexuality, I think, in its relation to this other tradition that I did mention, that of the Japanese wood prints which grew up as a medium in the prostitution district in Tokyo and that is where all of the great prints that are hanging on the wall of fine people today had their origin and retain their meanings if one attempts to investigate them historically and this is what they are about.

Their subjects is often prostitutes, specifically in that sense. I don't think it is beside the point to relate the painting, although it is a little bit difficult to read just exactly what the subject matter of the painting is, but certainly, that it accounts for its relationship to this kind of subject matter in the text of a document itself, I think it is an important example of a great revival of just there ancient concerns; that is, with typography with the broad sheet, with the idea of the single sheet of printed material that his circulated.

It has a very important sociological frame of reference that is essential to the real comprehension of what the work of art means in the socieity in which it is created.

Q--Now--

THE COURT: Well, let's see. You are talking about a work of art. Are you talking now about the manner of print, the type of print itself or the content of it?

THE WITNESS: I think one really has to relate to both of these together. I think it is very difficult to separate out the subject matter from the way in which that subject matter is presented.

BY MR. McDANIEL:

Q--Well, would you say, then, that both the form and the substance must be inter-related to make any kind of meaningful judgement about the material?

A--Yes. I am saying that they necessarily have to in order for us to fairly understand it.

In the somewhat broader sense of the real content of this which is more than the subject matter itself, a subject matter in this form, the way it is presented, yes.

MR. McDANIEL: May I approach the witness again, your Honor?

THE COURT: Yes, all right.

BY MR. McDANIEL:

Q--Turning to the poetry--

THE COURT: You haven't got off the first page yet. You have the headline, but what follows this? I think I get the message, but --

THE WITNESS: Uh-huh.

THE COURT: Commencing with "Whereby." Would you read that into the record.

THE WITNESS: "Whereby, on this day we able minded creators do hereby tell you, the Establishment: Fuck you in the mouth. We've heard enough of your bullshit. Let's have beauty."

THE COURT: Now, what does that mean?

THE WITNESS: Well, I think this does relate more to the substance of my concern with violence. I think it is in a violent statement for it suggests a certain violence of the spirit.

It certainly has revolutionary overtones. I don't take it too lightly. After all, I am a member of the Establishment, too. The State of California pays my salary.

THE COURT: Well, you are until your budget gets cut further.

MR. McDANIEL: Do you think that this is intended to apply to Governor Reagan?

THE COURT: Well, no. I don't mean to bring him into the case. He has problems of his own.

MR. McDANIEL: He has enough problems.

THE COURT: Not relating to the "Earth Rose," I am sure.

THE WITNESS: I think the two key words here to really figuring out what is the intent, if we can get inside of the head of the man who wrote it, which is terribly difficult, the two key words I would suggest are "Creators" and "Beauty," namely that "We able minded creators" --

This is clearly a statement encounter as a poetic expression. It is a statement of the man who is thinking of himself as an artist making a commentary on his time and I think that interpretation very well is substantiated by the text of the poetry contained inside.

BY MR. McDANIEL:

Q--Now, looking at the two large printed words "FUCK HATE," there, what is the meaning of that being in the large print?

A--Well, I would say that preceding the statement that I just read, it would be an imperative--it would in the common use of fuck, namely a statement about hate.

Q--Could you explain that please?

A--I think that this is a statement rejecting hate and rejecting it in a violent and impassioned way, saying "Fuck Hate. I have had enough hate. I have been overwhelmed by society."

That seems to be in many ways devoted to hate. It has as its ideal hate or hate which on all levels, on the personal level and the economic level and the military level, on the political level involves hate enough, saying that -- I am not saying that I necessarily agree with this expression, but I think that the first way that I read it, and that, in fact, is the way in which I interpreted this or submitted whit interpretation to a class of 400 students and my feedback from those students was that this, too, seems to be predominantly the way they would read that analogy, that I think that the first way to make sense of that --

THE COURT: Couldn't it mean, also, to embrace hate?

THE WITNESS: It certainly has an ambivalent reading there.

THE COURT: Yes.

THE WITNESS: I would say --

THE COURT: Embrace hate.

THE WITNESS: I think it embraces a far more gentle meaning than --

THE COURT: No. I mean it could be construed as meaning embrace hate?

THE WITNESS: That ambiguity, I would say, would probably argue for it being read as a poetic statement rather than as a strictly didactic comment, yes, as your Honor says.

THE COURT: All right.

BY MR. McDANIEL:

Q--Now, does that fact that the words "FUCK HATE" are in the large print there seem to you to make an attempt to tell people that what you are going o get in this document is a bunch of sexy writing?

A--No. As I say, my initial response to that was that I would probably find some material in here with decided revolutionary cast.

I don't really know that he would expect to find poetry in there, but this very ambivalence that the Judge suggests indicated that as a matter of fact when I just look up here to the next largest words in type on this front page, the "Earth Rose," I think of the ambivalence there, too.

The "Earth Rose" might refer to a flower growing out of the earth, and hence the nurturing of the earth to this poetic or artistic expression of it.

On the other hand, this can be read as a verb rather than as a noun, the word "Rose" and with this revolutionary overtone, that the earth rose up and her children made a statement of rejection of hate. So, in that way, the title and the statement could actually be thought of, I think reasonably, as tying together.

Q--Is it possible in the poetic media for meanings to be found in writings and poetry that the writer of the verse didn't even suspect was there?

A--Oh, certainly. If that weren't the case, I would be out looking for a job for one thing, and most literary historians would be, too.

But, actually, I think there was a poet who had the courage to make a statement about that. Wordsworth once said, "I take full and absolute credit for any interpretation anyone ever reads into any of my poems."

Q--Now, turning to the reverse side, not the inside, but the flip side of it there; how would you tie in this reverse side with the front side, if at all?

A--Well, the poetry as expressed at the same time, then, of what I would have implied here from studying the front side, meat poetry itself since I happen to be a little familiar with that tradition on the West Coast, is one probably developing in the mid-fifties. It is a whole school of poetry. Allen Ginsberg, Mike McClure, Lawrence Ferlinghetti, these people are involved although they don't use all that terminology. Mike McClure does for one. Meat poetry being poetry of the vista of poetry related to the bones and the flesh.

As far as Miguel deUnamuno, a great Spanish writer, was concerned, in Madrid I had occasion to study poetry, this is certainly not a phenomenon limited to the United States or California, but this concern with some attempt to bring poetry out of the academic world and place it down on experiences that are real for human beings, the perception of beauty and our terror in the world today.

As far back as the the 16th Century, the development of printing in Europe after Gutenberg, the development of wood block printing, for instance, or even in the far Eastern culture with the Japanese--well-known prints of the Japanese in the Nineteenth Century, particularly.

Perhaps I just didn't make the point

I feel that this expression is specifically concerned with the printed word, but also with the graphic representation more or less closely associated with the content of the printed word itself. It is something more integral in terms of the artistic concepts than seiplly an illustrated book, although that would be in the same line.

Q--Now, has some of this approach found its way into the popular culture of today, and by that, I specifically refer to the rock and roll phenomenon?

A--Oh, absolutely. In the lyrics of the rock and roll tunes, if one can ever hear the lyrics of them, there is plenty of evidence there.

Actually, a lot of the records are coming out now with lyrics printed on the back although a problem remains as to whether they are actually the same lyrics that are sung on the record, but the Beatles have done this, for instance; yes, I think you find that -- you find that in perhaps less violent expression in the Beatles' tune "She's Leaving Home," like saying an awful lot not only about the teenager, but also about America and about the relationship of the teenage daughters and the parents.

The fact is that the teenager who seems to be striving and grappling with reality even though they may not always be pleasant in the world and in their art form, rock and roll is one case in point that is essentially the teenage art form. The statements are being made.

Q--Now, how about a song like "Desolation Row"?

THE COURT: Like what?

MR. McDANIEL: "Desolation Row.

THE COURT: "Desolation Row"?

THE WITNESS: A Bobby Dylan song.

THE COURT: Well, I mean, I am not a hep cat, so I go back to Mexicali Rose. That is more my speed.

THE WITNESS: Yes. I wouldn't just single that out.

I think that singers like Bobby Dylan have made long indictments but ambivalent indictments of America. I think that is also very much of an acceptance of a deep concern with what is going on in society today and some attempt to come to terms with the problems not only personally by also as spokesman for the whole generation.

BY MR. McDANIEL:

Q--Now, you have indicated that in the meat poetry there refers to a type of school of poetry; is that correct?

A--Yes.

Q--Have there been various works in this type of vein of writing published in the last few years?

A--Oh, certainly, yes, a whole library of them.

THE COURT: You mentioned Ginsberg. He isn't the Ginsberg --

THE WITNESS: Well, there is several Ginsbergs. It is not Ralph.

THE COURT: Yes, well --

MR. McDANIEL: I think that is his cousin.

THE COURT: He was engaged in some kind of poetic endeavor.

BY MR. McDANIEL:

Q--You are referring to Allen Ginsberg?

A-- Allen Ginsberg, that's right.

Q--Now, is he a well known poet?

A--I would certainly think so, yes. He is a poetic hero of the current generation.

Q--Did he write a poem entitled "The Howl" at one time?

A--Yes.

MRS. NEW: I didn't get the title.

THE COURT: "The Howl."

THE WITNESS: Cadish's "Chorus of Sighing in Hell" and Ginsberg's "The Howl," "The Howl" was published by the City Lights Book Shop, I think, in the late fifties, '56, seven or so. This is perhaps the most widely read poem, the most influential poem to have come out of the San Francisco origins of this meat of poetry school.

THE COURT: Where are they located in San Francisco?

THE WITNESS: Well, they were centered around the City Lights Book Shop at Columbus and Broadway.

BY MR. McDANIEL:

Q--In North Beach?

A--In North Beach, yes.

THE COURT: North Beach?

THE WITNESS: This is before the Haight-Ashbury got started by several years.

THE COURT: Yes. The Haight-Ashbury is of rather recent origin.

I grew up there. It is my home city. Every so often I go up there. I like to keep track of what is going on up there.

BY MR. McDANIEL:

Q--Now, turning your attention to the inside, that it, the inside pages of the newsletter --

THE COURT: I haven't found out what this picture is about here.

BY MR. McDANIEL:

Q--Oh, first, perhaps you could describe the picture there so --

THE COURT: Well, I mean --

THE WITNESS: Well, perhaps I do the artist an injustice, but with my art historical point of view I tend to relate things to other things.

First of all, it is sort of a grim countenance, personally -- it is dark, a lot of shadows, a little bit ominous.

Myself, if were writing an article about this painting, art work of this artist, I would relate him to an English painter, Francis Bacon, who enjoyed a great deal of popularity, oh, starting about five or six years ago and in deep, strong initial representation, he represented England at several exhibitions, Francis Bacon whose paintings show the decaying or dismembering of people in fights, agony and extreme tension.

"Figure with Meat" by Francis Bacon

He has repainted not over the surface of the original paintings, but he has re-conceived a lot of old masters' paintings by people like Diego Velasquez. In a painting by Francis Bacon, people see an image of themselves terribly distorted in almost a frenzy, in a fight.

This does have a tradition, without boring you a great deal with art historical tradition, I think we should realize that we could take one example of, say, in the early Sixteenth Century Gruenwald painted a Crucifixion. He painted a series of Crucifixions for the altar at Isenheim, at Colmar. I think -- I am sure many of us would recognize it if we saw it here, but it shows the figure of Jesus Christ on the Crucifix. It is actually an almost scientific-medical study of a skin disease, a disease known as St. Anthony's Fire. It was an altar piece, a Crucifix altar piece for the monastery that was devoted to curing people of apparently incurable diseases and they would come there when all hope had failed and they would prostrate themselves before this image of Jesus Christ, which is one the most horrible and one of the most ugly, hideous and moving images. This was fundamentally a religious act because it was an act of subjugation before this image and, hence, a declaration of the fact that it was only through the grace of the Lord that they might be saved from their afflictions.

It actually showed Jesus Christ with open lesions with syphilitic -- syphilis was not understood. I had just been brought back from America and Saint Anthony's Fire, this other skin disease -- actually, I have talked to doctors who have analyzed the painting. It was some of the best scientific representations of it and here you have in the depths of suffering of humanity the most painful immediacy an image, painting, which is an image of the Lord Jesus Christ, profound and moving and totally overwhelming.

You can't call it beautiful, but you must call it art.

A detail from the Gruenwald Crucifixion

BY MR. McDANIEL:

Q--Is that type of statement applicable to this picture here on the back of the "Earth Rose"?

A--In a much less degree, but certainly the same in kind, yes.

Q--Is that, essentially, then, that one must find some type of faith in order to withstand the pain of existence; is that about it or what?

A--Yes. We can interpret this as historians -- I think it is a little dangerous to try to inside the head of any artist, but I think that you have to do that.

Looking at the evidence of this kind of painting, I think it would be fair, and probably to understand what the artist is trying to, it would be necessary to approach it on this level. I think this is a valid one. I think it is necessary one.

Q--I see. Now --

THE COURT: What is its relationship to meat poetry?

THE WITNESS: I think this is very much the same kind of substance here in this. These poems were taking subject matter from the reality of existence.

I think here, too, you find a painter taking as subject matter -- it is not an abstract painting, you see, and for 50 years now we have the possibility of painting abstract art. I think it is significant that the artist has chosen to paint subject matter, to paint human beings, to against what might be the fads or later directions of painting and to stick his neck out on this statement. I think that simply reaffirms his commitment to very difficult human existence.

I think -- I mean, we live in an age where everybody -- we can go home to the television set and we see men being killed on our television set in our living room. The fact that some young artists are impressionable enough to be moved to represent this or to attempt to represent the substance of this kind of experience doesn't amaze me at all.

CBS reporter Dan Rather covering the Vietnam War in 1968 on television.

THE COURT: You think that is the reaction this average person would get from looking at this thing?

THE WITNESS: Well, I started off to try to set this in some kind of historical context. I certainly do not think the average person would put it in that context, but one can make a very strong case as an art historian from that, from Gruenwald in 1512 all the way up through the people like Francis Bacon of a dozen years ago to this, you find a constant and this kind of artistic attempt.

I think that the average person looking at this and going home and turning on his television set and seeing a film of Vietnam would make a distinction, and I think people who do that get very close, probably, to the artistic intent motivating it, yes.

BY MR. McDANIEL:

Q--This would be, then, in your terms, an attempt by the artist to force a person into an awareness of the fact that killing and death is not good; is that right?

A--Yes, and it occurs to me that this is one level of interpretation that definitely links the back with the front.

It can -- if I could turn for a moment to the inside without --

THE COURT: Go ahead.

Chaim Soutine's "Carcass of Beef"

THE WITNESS: -- without going further into this, let me simply suggest two painters that come to mind with the painting inside and they are Chaim Soutine, who was a Lithuanian Jewish painter in the early part of this century, and he is just about to enjoy a first major exhibition at the Los Angeles County Museum of Modern Art. The Curator Maurice Tuchman assembled the show. He is one of the few painters who painted decaying flesh and meat while he was starving to death. He would continue to paint day after day the process of the decomposition of a side of beef in his house. Instead of eating it, he painted it decaying.

THE COURT: He was alright, otherwise?

THE WITNESS: Well, his paintings are all right. I mean, whatever his biography.

It is quite clear there are some men who perhaps may be mad men, but the fact is that they do produce very moving works of art and I look forward to seeing this exhibition when it opens next month at the museum.

THE COURT: All right.

THE WITNESS: Soutine certainly wasn't the first artist to do this kind of work.

Let me suggest another one who is an absolutely solid citizen. He had invested in the local industry. He was a merchant and married to a family of merchants and a fine painter in his own right who chose among other subjects decaying sides of beef and his name was Rembrandt.

BY MR. McDANIEL:

Q--But at least he ate his meals?

A--He probably ate a bite or two first.

THE COURT: I expected you to say Swift.

BY MR. McDANIEL:

Q--Well, now, there are also people like Hieronymus Bosch, I suppose you could tie in there, is that correct?

A--Not with this particular imagery, but there exists paintings which this relates directly, I think, of Soutine and of Rembrandt. These paintings, I am talking about the visual image.

Q--Right.

A--If we talk about the image of poetry, Swift didn't come to my mind. I think he could. He is easy to read into this context, but some of the imagery that is referred to or referred to in this poetry, I think does come vey close to the sense of Joachim Patinir, Hieronymus Bosch, of Peter Brueghel, a whole series of people with apocalyptic vision in different ways and more fantastic ways, more ways involving the fantasies than an artist like Gruenwald who is almost a very sacred vision.

Q--As an apocalyptic vision, does that term relate in any fashion to the "Earth Rose"?

A--Yes, I think so. The apocalyptic vision, the vision of the end of the world or the destruction of the entire cosmos, of the universe, and, of course, stems from the apocalypse, the final book in the Bible, in effect, does have this sense of the earth rising, so, I would say strictly speaking, you might have that, that the spirits of the dead would rise up from the earth and then descend and --

Q-- I see.

A--In that sense, in a more general sense, I mean, some sort of an exit of Jesus in the apocalypse.

I think that you find the imagery is parallel to that in the book of the apocalypse and that the whole sense of this whole spirit of this in the general sense rather than any specific imagery relates to painters like Bosch.

Q--Now, looking at the inside of it briefly, before we talk about an individual poem, we have been over this material several times and you have noticed that there is a lot of use of what we call the four letter words, fuck, shit, piss, cock and so forth.

Does this use of these words in this poetry have some special meaning that necessitates the use of those words? What I am trying to say by that, is there a legitimate artistic reason for incorporating that type of terminology into poetry in this fashion?

A--My feeling is that these words are chosen for their expressive, associative value but in a way that removes them perhaps from a concern with normal sexual relationships and takes them as poetic encounters.

I think that these words are used not with an intent to describe any particular sexual act, but because they are strong words, because they are, after all, ancient words in English and because they are such powerful words they still create in us some kind of a sense of an an awakening, an awakening of our intellect when we read this.

Curiously enough, I think that the reasons for this poetically are much more concerned with social and political statements than they are with any sexual statements, so that in a sense, although these words themselves have definite sexual associations, that is the motive power which has occasioned their selection in this this to create this new context where other wider statements are being made.

Reading some of these poems, for instance, I think it becomes very difficult, whatever we may feel about the possibility of reading about an embrace here, and I don't get that feeling. I think it is immediately dispelled when you read the poem "Freedom."

Q--Let's take the one called "The White Geese Flying South" there.

A--Well, it is North on my page.

Q--North. I am sorry.

THE COURT: That was the south end of the goose flying north.

MR. McDANIEL: I suppose I was thinking of the Tijuana Bible and so forth.

THE COURT: Or Mexicali Rose.

BY MR. McDANIEL:

Q--Now, have you ever seen material know as Tijuana Bibles?

Examples of Tijuana Bibles

A--What do you have in mind by that? I am not --I have -- what are you -

THE COURT: Do you want a Bible?

MR. McDANIEL: It is a cartoon joke book showing sexual activity.

THE WITNESS: Yes.

BY MR. McDANIEL:

Q--Have you seen Stag motion pictures?

A--Yes. Only in my professional capacity as a an art historian, though.

Q-- I see.

THE COURT: Well, now, that is a voluntary statement that should be stricken. No it will remain in evidence.

BY MR. McDANIEL:

Q--Also, before we into the poetry, I will ask you a series of questions.

THE COURT: The next question should be, were you ever in a place when it was raided?

MR. McDANIEL: I didn't catch that.

THE COURT: The question to follow that, if you are going to inquire about stag movies, then, the next question is: Were you ever in a place when it was raided?

BY MR. McDANIEL:

Q--Or did you ever participate in filming one?

A--No.

Q--Have you read some of the works of Henry Miller?

A--Yes, indeed.

Q--Specifically, I am referring now to the "Rosy Crucifixion" and "Trilogy of Sexes."

A-- Yes.

Q--Have you also read the work "My Life and Loves" by Frank Harris?

A--Yes.

Q--And have you read parts of the work entitled "My Secret Life," author unknown?

A--Yes, parts of it. That is something like the Warren Commission Report, 26 volumes. Parts of it, yes.

Q--I see. Now have you read --

THE COURT: We are not going to get into that, are we, the Warren Report?

MR. McDANIEL: That will come in later in the next series. We will call Jim Garrison on that.

THE COURT: All right. We will have him called.

MR. McDANIEL: I don't know if they will extradite him for this though.

BY MR. McDANIEL:

Q--Now, with regard to the work "Naked Lunch," have you read that?

A--Yes.

Q--That is by William --

A--Burrows.

Q--And did you read the work "Candy" by Terry Southern?

A--Yes. Mine was by Maxwell Kenton, I think.

Q--It was a pseudonym he used. Same book, yes. Now, did you find the same words such as fuck and piss and so forth used in the books that I have mentioned?

A--Frequently.

Q--Thinking specifically now of the Henry Miller "Sexes," did you find that the use of the words there with a seeming intent to do something far different than the way they were used in the "Earth Rose"?

Hieronymus Bosch panels, Paradise and Hell

A--I think the use of Miller of those words is very similar in intent. Now, Miller is one person I would call an apocalyptic writer whose vision of the world through his own sexual experiences real or fantasized as they may be, comes very close to his depiction of the early "Paradise Expelled Panel of Hell" by Hieronymus Bosch. I think they are very similar in fundamental intent, yes.

Now, Burrows, I would say, is another experience for different reasons, too, certainly with Burrows' use of narcotics.

THE COURT: What is the title of his book?

THE WITNESS: "Naked Lunch."

BY MR. McDANIEL:

Q--Is "Naked Lunch" similar to the meat poetry or is it a different classification?

A--Well, I wouldn't relate it to meat poetry very specifically, no. It is of that same period, but simply because it is a much -- it is a big book and it would be -- maybe you would like to call it a beat poetry.

Q--I was thinking of meat poetry. Not beat poetry.

A--Oh, meat? I am sorry.

THE COURT: Meat or beat?

BY MR. McDANIEL:

Q--There is a difference?

A--Yes.

THE COURT: I mean, there is a difference between the two.

THE WITNESS: There is a difference, indeed.

Beat, I think, would be the more generic term referring to the people who did or did not write poetry.

In fact, it is interesting that the beatniks or the Beat Generation of the fifties was still very oriented to the printed word. They were still literary people, whereas, you know, the hippies of today, although some of them can read, very few of them do.

THE COURT: We are dealing with two traditions.

BY MR. McDANIEL:

Q--Do you find that this implies progression, then, or is that too far afield?

A--Well, I think that is in a sense -- some might call it old fashioned. It is certainly standard tradition and there are wilder things going on in terms of visual imagery that are suggested by something like this which is very conventional simply by its format.

Q--I see.

A--That has to do with the customary standards, I guess.

Q--Now, taking a look at this poem, "The White Geese" poem flying in whatever direction, could you read that over briefly and could you please explain to the court as best you can what the point of the particular poem is, what it is telling us?

A--It is interesting. The subjects, the professions that are mentioned here touch on several of us in this very room.

THE COURT: Yes. I can understand the one about the lawyer.

THE WITNESS: Oh, I see. I was reading the one about the limp professor in the academy.

THE COURT: You see, we all have a thing, don't we?

THE WITNESS: Something for everyone, for the priest, the rabbi and the father.

Yes, I think that structure of the poem is fairly simple, that a series of images are cited and people go about their tasks in the world as we know it, people we usually think of as upright people, as respectable people from the milkman or the beer maker, the farmer or the butcher or the doctor, all the way on down.

The psychiatrist, of course, is the last and presumably the highest in repute and --

THE COURT: In where?

THE WITNESS: Well, I assume this an ascending scale of social virtue.

THE COURT: Well, maybe by the time he got to there, he went to the couch.

THE WITNESS: The $25 an hour psychiatrist is not, not really the top of the profession by a long shot, but I think the clue to the meaning of this poem does reside in the last line, "No! It's to be seen Here!" with a capital H for "here" which would set it outside all those situations that are cited.

The one profession that I assume is closest to the writer himself is that of artist and there is nothing said about artists or poets --

THE COURT: No.

THE WITNESS: -- here and I would assume that this is a plea for the validity of the artistic imagination. The power and the meaning that can be be contained in the poetic statement, it is to be seen here, here in the terms --

THE COURT: You mean this is poetry?

THE WITNESS: I would say it is poetry. My interpretation of this by virtue of this last meaning but setting it in contradiction to these others it is proper or "It's to be seen Here!" are the words of the poet. "It's to be seen Here!" as physically, graphically on this sheet, this is sheet of poetry. "Not in a pigpiss image of white geese flying somewhere" which is also a revolutionary statement about other poetic forms as opposed to another poetic spirit.

BY MR. McDANIEL:

Q--Well, isn't that the last line in here saying something about what we might call transitional art, academic poetry?

A--He sees life as an indictment, as a rejection of it.

Q--Explain that please.

A--Yes. "No. It's to be seen Here!" meaning the poetry on this page or the kind of poetry in the imagination of the writer in meat poetry as a school, "not in a pigpiss image of white geese flying somewhere" which has set up this image which is a very lyrical image, very typically poetic image, one I think that none of us would have trouble seeing as poetic.

"White Geese Flying North" is very beautiful. The poet uses that image to relate to the realities of our world as to each of the professions, they are selected, of source, but they mean, I think, to imply after all that the world is not concerned with aesthetic visions of the world and they are rejected because they are shown side by side with ugliness, with ugliness and hate and not beauty. The "White Geese Flying North," whatever we like to do in beleiveing this is pretty ourselves, it is a rejection.

A parallel would be Gruenwald. Here is a perfect rejection in a general way in the pale pastel colors.

Q--I see.

A--The real quest of the real spirit in the man of the world today.

THE COURT: Is that what you get from this?

THE WITNESS: Yes.

BY MR. McDANIEL:

Q--Now, taking your attention to the comments you just made with regard to this concept of traditional poetry, pretty words and images --

A--Yes.

Q-- --could you please explain to the Court what the current thinking of academic scholars, students of the field of art is, with regard to what the proper function of an art, specifically poetry, is or how would it be defined today?

A--I think the the statement about the limp professor in the academy is manifestly unfair. In other words --

THE COURT: What do they say about that?

THE WITNESS: Well, "His balls cut off and he knowing it, living off it," well, is certainly true in some special cases.

My answer to your question is that there is probably a great many more professors in the academy who understand this position, who understand it very well, because of their humanistic training and because of the training in the history of literature and who see this is a normal encyclical response, the new generation of poets and who not only understand, but who accept it and who can make sense out of this.

In other words, I think there is a great deal more professional and academic sympathy for reading the poem the way I read it as a statement rejecting past hallowed traditions. We have seen this over and over again. I think there are many professors who would come to the same understanding of this as I have.

THE COURT: What do you get out of it? Why was it necessary to have the balls cut off?

THE WITNESS: Well, I think that is pretty obvious it means for a lack of courage, lack of conviction, lack of men to stand up.

After all, it is very competent job to be a professor and we are more protected than most professionals in society and yet with all that freedom, it is surprising how few men do have the courage of their convictions. It is much easier to sit back and say all the right things.

Nevertheless, there are many people, many professors who do say things of importance, who do specifically, I think, understand this kind of statement about rejection of past forms who have have written about it, who have understood it. Playwrights such as Antonio Arturo who said very nearly the same thing in his rejection of the conventional theater and his quest for the theater of cruelty.

THE COURT: Why didn't he say that?

THE WITNESS: Why did Arturo say that?

THE COURT: No. Why didn't he express this thing?

THE WITNESS: Well, the writer of this poem?

THE COURT: Yes.

THE WITNESS: Yes, because I think that while there are a few courageous professors, the odds of him coming across one of them is slim.

MR. McDANIEL: Let me interject here, your Honor, that I intend to call the author of this particular poem to the stand after Dr. Von Meier is through so we can get that.

THE COURT: Well, all right. All right. Then I shouldn't be interrupting. Go ahead.

MR. McDANIEL: No. I don't mean to say you shouldn't be interrupting at any time you want to, but I just wanted to say that I do have the author of that poem here so he will be on the stand later.

THE COURT: All right.

BY MR. McDANIEL:

Q--The question I meant to ask, and I don't think it was phrased properly and that is this:

Is there a definition of the art of poetry and other arts sort of lat large today in the world that is contradistinguished from more or less traditional depictions of, let's say, poetry as an elevated statement of beautiful images and if this is true, could you please amplify that?

A--Yes. I think there is and this distinction, this definition is not an entirely new one, of course, but I would say the prevailing academic opinion about poetry would relate to a statement by -- I think Ezra Pound quotes it. It is called "Dichter Condensare." A German sword, dichter, to which the poet tries to write, condensate, an Italian verb meaning to condense, to make tight.

Pound writes about that in his literary essays. This is in essence the function of a poet, to compress, to condense in the medium of words his feelings, his statements, his understanding about whatever subject in the universe he is writing about and to put this into some form. Poems today don't have to rhyme, and there are very few professors of literature that would claim that they would have to.

Q--Then, in terms of poetry, what you would be saying there would be that, for instance, as it relates to the question that his Honor just put to you, it is the function here of the poem to, by a limited number of words, bring a whole vast are of experience and interpretation of the experience to a reader if he can interpret it; is that correct?

A--Yes. This is really what I meant to convey in that my suggestion that the picking these professions he, one understands very soon that his is really talking about society as a while and that he wants to make his statement which, as I say, the statement is condensed into one line at the very end after setting this up.

Q--Now, isn't the poet or the artist supposed to limit himself to aspects, words and descriptions of an event that evoke a nice sort of pretty feeling about things? Isn't he supposed to reject the ugly and coarse and search for the beautiful in his work?

A--This is precisely the question the poet seems to raising in this poem, the rejection of these images, these "Pigpiss image of white geese flying somewhere."

Flying somewhere? Flying where? I mean, it is the image of that instead of the validity of the statement, the meaning of the relevance of the poet. It is these poetic forms that he employs hollowly and this practice of what goes here for, I guess, academic poetry that he is rejecting.

My comment, and maybe I just got a little too far ahead of myself or I lost the trend of it, is that this attitude itself forms a tradition and there are many poets and there always have been -- one could say that Shakespeare as a poet conveyed precisely the same problems which were different terms in his day.

He had a rejection, the same formula the poet tried to insert in here for the individual as a human being as a poet in the image he created. That is really just an essential statement about the artist's creativity and originality.

Q--Now, some of the inferences to be drawn from this particular poem would seem to be the essential stagnation or meaninglessness of a lot of contemporary life; isn't that true?

A--Yes, and a lot of contemporary poetry, too.

Q--Now, if you take this and you look at the fact that he uses this rather harsh and offensive imagery, the words such as fuck, the pigpiss words and so forth, could you explain if it is at all possible to, some explanation why that is a situation that should be allowed to the poet when you have such examples of people like T.S. Eliot writing "The Holyman" or "The Wasteland" essentially about the same type of stagnation, but limiting themselves to the more acceptable form of imagery?

A--Well, I think that the imagery tends to change and probably good good reasons for changing when the conditions in the world change.

I mean, after all, we live in an age of atomic power. We live in the age of the H-bomb which T.S. Eliot didn't have. We live in the age of Vietnam. I think it is important we take "Vietnam (a flexible title)" I see it, without having read it in that context before, that as long as there is a Vietnam, as long as there are Crimean wars, you will find poets of times writing about them. As long as there are human problems, you will find poets and artists who intend to get to the core of the matter of human experience.

Q--Now, taking an analogy from another segment of the arts, in terms of what materials or what areas the creator in any sense is going to allow himself to employ, does John Cage have any light to throw on this area?

A--Yes. Let's see. I hadn't originally thought of John Cage, but Cage is an advantage garde musician who has concerned himself not only with electronic music, but also with the problem of basic distinction between music and noise; that is, what the fundamental question is, what is a should and what is a sound that makes it acceptable in the context of a a work of art, music, or not acceptable; that is noise.

Cage who does write and writes quite eloquently has written essays about this, but also has made statements in the context of his music. Now, his music has used recorded noise and what we would hear, and I think most of us would understand as noise, but put it in a fine art situation and, so, he is taking elements from the real world that are not traditionally accepted or one doesn't immediately respond to them like I imagine just in terms of conventional images, but here not visible images but not conventional images but the qualities of the sound, recorded sirens or traffic noises and brought these into the concert hall, when we hear whereas all of us who have sat in a concert hall, when we hear traffic noises outside we tend to look at them as distracting.

Cage has said that essentially all sound is capable of being music if it is conditioned and presented and controlled by the artist. Passing through that medium of the artist, he presents it, and, then, we can open our to an entirely new potential of the beauty in the world or meaning.

Q--Now, taking that point of view and relating it to the use of different metaphors in image poetry, would you say that has some relevance to the issue here of whether or not the poet should use these kind of garbage can images?

A--Certainly it does in theory, but I think the cases between music and poetry are different historically; namely that Cage's statement is much more radical in the terms of historical music and fewer people have done this before him, whereas in poetry, there is a very long and venerable tradition of this back to, my God, Roman poets like Petronius.

I mean, for example, we can go all the the ay through the history of literature and we find this is a common practice among the great poets. Shakespeare himself used real words from the real world and to use these in the context of his poetry, yes.

Q--Now, the use of the words alluding to the sexual activity and done in the most candid fashion of the times is a tradition that is very popular in poetry; is that correct?

A--Yes, indeed.

Q--And is it true that some of the really great writers of the past, such as Chaucer and you mentioned Shakespeare, I am speaking now just of the English language poets --

A-- Yes.

Q-- --have certainly done this themselves?

A-- Chaucer and Miller are well know, surely, all the way through, though.

Q--If we just turn for a minute to another specific poem, one of Buckner's poems, the tip right hand poem called "Coughing," if you could take a moment and look at that one, again, I will ask you for an interpretation of what that poem seems to be saying.

A--In this statement of intimacy with God, there are parallels, indeed very close and explicit parallels not identical, but very very similar of sexual conference with the Godhead in the mystical poetry of Saint Theresa of Avila. This is in Spanish tradition. It is not poetry in English, but it has certainly been translated into English as is part of a long tradition of Catholic poetry. This is just one that comes to mind immediately upon reading it.

Q--Well, what does the poem really mean, though?

A--Well, I think it is challenging the conventional image of God, for one thing, when it says -- refers to God and then, refers to God as "She buried it so deep."

"She buried it," I presume God's cock is being referred to here, a statement obviously an absurdity. In the first place, in the sexuality of humanity as we know it she would not have a cock. So this is something that is outside our real world, an experience so strange, so incomprehensible to use in our worldly terms that it really is a metaphysical statement.

That is the only way you can make sense out of it but on that level, you can and it is quite explicit. We don't ordinarily think of God as she, but certainly if God is she, then she can't have a cock if we are talking about the real world.

So this is a metaphysical statement, but it is also a statement about the mystical. I find parallels in the tradition of mysticism in this. I think of it in terms of the immediacy of the experience of the spirit of God or the will of God and, hence, this act which is symbolized by our sexual act.

Sure, that is the imagery that is used and it is not the first poet to use it as a subject. There are many others. John Dunn is another case in point in the English tradition.

The last line suggests yet another tradition without going too far afield but "Gulping down columns of night air." "Gulping down," this is two acts that lead to coughing, the title of the poem, as taking something in the mouth. Now, here in one case it is God's cock and int the final case, it is night air would imply, I think, a pantheistic reading of this that is God but not God as we conceive Him all abstract, but God also as a world God who can manifest himself in the form of night air as well.

So, you know this relationship to night air, you know as well as to an idea.

Q--Does it seem to mean anything at all about the condition of the person that is being described there, the person that says "I am sick" and, then, goes on through the various images in terms of the some type of desire for understanding of the the experience or anything like that?

A--"I am sick" may be a present condition of dissatisfaction with the state of the world today. It may be much more explicit in its relationship to the milkman who secretly pukes in the bottle, this type of sickness, but it may refer to a spiritual condition, too.

This ambivalence is not, I think, a lack of the force in the poem as much as a richness of the possibility for interpretation, but if you start off sick, and then, somehow seem to be purged or come to a confrontation of God or some experience however private and personal it is. I think one of the keys here may be the statement -- may I read this?

Q--Certainly.

A-- --to make sense out of what I mean here. "I am shit," the total deprecation of the self. That is in a submission to God's will and I think this would be a very --

THE COURT: Why don't you read it the way it is written and see --

THE WITNESS: Okay. "I am shit sucking" --

THE COURT: No. Start with "I am sick."

THE WITNESS: From the top?

THE COURT: Yes.

THE WITNESS: "I am sick. I swallowed God's cock: twisted my neck into my own mind, she buried it so deep I many never get it out.

"I am shit, sucking my own cock. I can't escape what was. I keep finding myself wanting to trick fuck myself, shrieking silent shrieks, gulping down columns of night air."

THE COURT: All right. I can follow your reading, but I can't follow the writing.

BY MR. McDANIEL:

Q--I want you to try to explain keeping on this one poem.

A--Uh-huh.

Q--First of all, in terms of what you have said about an abundance of images and possible interpretation--

A--Uh-huh.

Q--is that present or does that say something about the significance of the poem just in terms of starting to analyze it from that point of view?

A--Generically, it certainly suggests that it is well within the definition I suggested before of poetry, a concise statement that is rich in possible readings and meanings.

Q--Now, there are many ways that this poem could be interpreted; is that correct?

A--I think so, yes.

THE COURT: And decisions of the Supreme Court.

THE WITNESS: A difference reading that is possible is the identification of the self with God, the perception of the spirit of God that is within every human beings and this is documented, if you like, in the poem by "Sucking my own cock."

When it is cock, that is God's cock that can be set alongside. That is a parallel that, in other words, the God that he has been talking about is not a god that is up there our out there, but a god that is within myself.

"Trick fucking myself," that this is all an internal problem, a problem of thoughts that are going on and the concerns with the individual human being and as if to say that God can only be perceived in and through ourselves.

Now, that would be, I think, a different interpretation but one that can be sustained by the words but it would be different from the two others that I already suggested; namely, that the god as a metaphysical concept, hence with the dichotomy here, the paradox of God being a she and God, she having a cock and the pantheistic nature of the interpretation of God as the night air.

BY MR. McDANIEL:

Q--Now, does the poem seem to be a poem to you that shows a large degree of control of images on the part of the poet who wrote it?

A--Well, I would have to say so simply standing behind my own interpretation here.

Here the thoughts have progressed and even these paradoxes, I think, can be read as a progression of the thought of the poet through the poem. It is important it starts out with a title and that one wants to examine because here is a condition, an experience, an immediate experience, coughing. Now what does this mean? What does this mean to the poet? "I am sick."

That is just an immediate interpretation of it, well, and that is adequate except that the reasons why I am sick. "I swallowed God's cock." Incredible statement. What does this mean? So I think that the control in the step by step that this is a very -- it is very understandable to me in the terms for the aesthetic structure of this as a poem. It is not to say that is the only way is could be written, but I understand it this way, yes.

THE COURT: Who else would be expected to understand it this way?

THE WITNESS: I would expect any of colleagues at UCLA who have any sort of sensibility or training in the history of literature, but not that their interpretations would agree with me, but I think in terms of the poetic structure of it.

THE COURT: You mean they substantially agree with you?

THE WITNESS: Yes.

BY MR. McDANIEL:

Q--Do you have any way at all of trying to decide what the average reader would make out of this?

A--I think the average reader might be perplexed, but I think the average reader would probably be most perplexed about what the poet meant by God and what are these conditions in which God, the idea of God is being set.

I rather suspect the reader would focus on that more than what any sexual references it might have because of the the juxtaposition of the Godhead who is in a conventional way--the man in the street would not immediately relate God, I think to sexual activity, though he very well may do that in the privacy of his own bedroom, still would be perplexed by this; that is, I can't hypothesize much more than that.

I think that would stop him right there and mange him begin to think about it, in which case probably to poem would have been a success for the poet even then.

Q--I see. Does the poem itself admit as a possible interpretation, the limited one, that is just an excuse to throw some four letter words together?

A--Most certainly not.

THE COURT: You mean under no circumstances would anyone give it that interpretation?

THE WITNESS: No. I think -- I think that the people who would most strongly object to it would object to it, as I suggest, on the basis that it was an excuse to use to some four letter words. It is three letter words, actually.

THE COURT: Oh, we don't have to concern ourselves with the number of letters in the words anymore.

BY MR. McDANIEL:

Q--Let's take a look now at the poem in the lower left-hand side, "True Story."

THE COURT: Why don't you go down the page and we will finish up with that page.

MR. McDANIEL: I think we have to do it crossways.

THE COURT: All right. Do it crossways. All right.

MR. McDANIEL: Because all these things inter-react.

BY MR. McDANIEL:

Q--First of all, before we get into this, you have studied this document many times, isn't that the fact, Dr. von Meier?

A--Yes.

Q--Is it true that there seems to be a type of logic to the arrangement of the poems on the page?

A--Yes, I think so, but this is -- this is all my own interpretation. I don't know how much -- you might well ask the poet about this, but I think that for one thing, it suggests a kind of concern with mosaic structure rather than with a lineal structure. In other words, that we are perhaps not inclined to start on the upper left-hand corner and read across or down or read scrolls the page that way and in this way there are very general frames of reference.

I don't want to get into themes unless somebody does have questions about this, but that is a type of alternative of the construction of a work of art that parallels this. The Eisenstein theory of motion was used by Ezra Pound in the structure of the canto which art critic Allen Tate has analyzed in great detail so that I think that -- let me say that --

THE COURT: All right. Let's get on with the "True Story," then.

THE WITNESS: Yes, indeed.

BY MR. McDANIEL:

Q--Now, if can just take a few minutes to look that one over, I would like to know if you can give us a linear sample interpretation of the meaning of that poem -- first of all, before you answer that, let me ask you more questions.

Is it true that the search for one specific structural or stochastic meaning coming out of a poem is a vain search, normally?

A--Essentially, yes. To look for the one meaning -- well, as I said before, any work of art and including poems and specifically poetry since we are talking about it here is poetry because it affords multiple interpretation, because it will have enough flexibility to retian some sense of meaning for different people who read it. These meanings, of course, will be differently interpreted.

Q--Right. Now, what does the point, if there is a general point, about this one seem to be, the "True Story"?

A--I see -- I see this -- as I am not particularly -- I don't want to cast a religious interpretation on these poems -- following "Coughing," I think a religious one as, for instance, the self castration which goes back to Saint Origen who castrated himself and martyred himself and this is the first level on which the poet is writing autobiographically about this symbolic castration or which is a real castration, the case of Origen which in the poem is the real one, "Walking along the Freeway" which immediately sets it on contemporary society, even in Los Angeles, if you like, and as freedom march. The word freedom march in the next to last grouping of words there, a one-man freedom march, I think for me, is the dominant theme that is conveyed here and that is a statement of freedom that is being demonstrated which is a concern of Charles Bukowski throughout his poetry and, in fact, the pit of this poem is a plea for freedom, freedom in relationship to the ancient problem of free will of the human being who experiences this, not in terms of the conventional God, not as a theological argument, but more as a practical problem of his day and an exercise in the very structure of the establishment of the State and in the sense, it is in perfect accord with the statement about the establishment.

I am not necessarily in total agreement with it, but I say it is in accord with it and makes the statement in the terms of the statement about the establishment on the cover here and this has a protest. The word protest is used and a protesting against everything, but this is everything embodied into the form of the State.

It is a one man freedom march against the State and doing it through a symbolic gesture of castration.

Q--Now, this poem by ---

THE COURT: Carrying his parts in his pocket instead of a banner?

THE WITNESS: Instead of a banner, right, which, after all, would be a a more dramatic way.

THE COURT: Yes.

BY MR. McDANIEL:

Q--Now, "At work" is by Charles Bukowski. Are you familiar with the works of Mr. Bukowski?

A--Yes.

Q--In general, would you explain to the Court a little bit of what you know about Mr. Bukowski?

A--Well, what I would like to explain is simply -- Bukowski, I think is a good poet. I don't think he is a great poet, but I think he is typical in many ways that he expresses his concern with man's social existence; that this is -- well, I hate to say primeval, but among other things a social document concerned with man's own personal freedom in a State that is increasingly anti-human and anti-individual and that this is tied in with old concepts of God, that not only the literary -- I don't know whether Mr. Bukowski had had Origen in mind in terms of the self-castration, but certainly the theological or traditionally religious level verified by noting the last stanza, "God or somebody else bless him."

This is a question of existentialism or a quest for God or for something of a higher meaning of the section, "Along the Freeway." I would say this is dominant theme throughout Mr. Bukowski's poetry that is very much a social poet, as well as a lyrical poet, is concerned with his own problems of God.

Q--Now, has he been published in the various formats that you know of?

A--Yes.

Q--Let's go back to "To Be Outside" by Mr. Buckner. One first question is noticing the way the typesetting is there in sort of a triangular form. I that done for some specific reason?

A--Yes.

Q--Has that type of typesetting been seen in other poets before?

A--Yes. Perhaps the most famous example of this will be Louis Carolus. The setting of the type in the special format in the words where the type curls down like the tail and the single word. This also fits in the general statement that I made concerning typography.

He comes among the American poets who have been obsessed by the way their poems look on the page. Their typographical impact has every bit as much as what their subject matter of the words are.

THE COURT: All right. Well, that is a matter of typesetting. Is that about it?

THE WITNESS: Yes, but it is matter that is specified by the poet.

THE COURT: All right.

THE WITNESS: It is not simply left to chance.

THE COURT: All right. We may not be in favor of that way of setting type. All right. Now, the next question.

BY MR. McDANIEL:

Q--Now, Dr. von Meier --

THE COURT: Or do you -- you mentioned taking a lunch break a little while ago. Do you think it is time to have a regular lunch?

MR. McDANIEL: Yes, I guess so.

THE COURT: How long do you wasn't to take for lunch? I will let you people decide. Do want to return at 2:00 o'clock? Are you going to have enough time today?

MR. McDANIEL: Let's say 1:30. How is that?

THE COURT: All right. That is all right. That gives us an hour and five minutes for lunch. We will recess until --

MR. McDANIEL: Your Honor, may I inquire of my witnesses, Dr. Markman, do you have obligations that you have to fulfill this afternoon?

DR. MARKMN: I have, but I will cancel some of them.

THE COURT: If we are going to put the author on --

MR. McDANIEL: Well, we will get our witnesses today.

MRS. NEW: I don't know.

MR. McDANIEL: Your Honor, I am going to be through with Dr. von Meier rather rapidly after lunch. I would try to do as much --

THE COURT: Well, I will stay here so far as I am personally concerned, I will stay the remainder of the day. I should say, the remainder of the day, I mean, 4:30 or 5:00 o'clock or so.

MR. McDANIEL: I am sure we can get through with the whole thing by then. I will try to speed this up as much as I can.

THE COURT: All right. Then, that is the understanding.

(Whereupon, a noon recess was taken until 1:30 p.m. of the same day, Friday, February 16, 1968.)

SANTA MONICA, CALIFORNIA, FRIDAY, FEBRUARY 16, 1968, 1:40 P.M.

THE COURT: All right. You may proceed.

MR. McDANIEL: Could we have the last question from the reporter, please, your Honor?

THE COURT: Yes. Read the last question.

(The record was read by the Reporter)

THE COURT: Was that sufficient?

MR. McDANIEL: Yes.

DIRECT EXAMINATION (CONTINUED)

BY MR. McDANIEL:

Q--Now I believe you have already testified that the use of this type of imagery, words like fuck and turn and so forth, exists throughout a broad range of literature over the last many, many years. Is there an example of this to be found in the work of C.J. Jung?

A--Yes, indeed. Not in the context, necessarily, of a work of art, but in a more fundamental context where Jung, who is, after all, one of the great psychiatrists and founders of psychoanalysis along with Freud concerned with the basic problem of human behavior and the established human behavior patterns, and in this context Jung does have a rather vivid and terse description of an early and moving childhood experience, a vision of God which is contained in a book, "Memory, Dreams and Reflections."

It is to the point, I think, in that it relates to a great deal of imagery here and perhaps it would be possible just to read one of the short paragraphs?

Q--Is this the work here, "Memory, Dreams and Reflections"?

A--Yes it is.

THE COURT: Very well.

BY MR. McDANIEL:

Q--Is this book for sale on news stands throughout the country?

A--Yes.

(The witness examined the book.)

THE WITNESS: Jung is recounting experiences which he cites as a moving and determining influence throughout his life, leading him eventually to him -- leading him to follow the career of medicine and psychoanalysis, specifically, and for several days as a schooolboy he is obsessed by a vision, a vision that involves God, involves God sitting in the clear blue heavens upon a golden throne and shows how he stopped from going in further to realize what this means to him.

He cites, again, his urge and a tendency to pursue this thought, and finally he does.

"I thought it over again and arrived at the same conclusion: Obviously the God desired me to show courage, I think. If that is so and I go through with it, then, he will give me his grace and illumination.

I gathered all my courage as though I were about the leap forthwith in the Hell fire and let the thought come. I saw before me the cathedral, the blue sky above it. God sits on his golden throne high above the world and from under the throne an enormous turd falls upon the new roof and shatters it and breaks the walls of the cathedral asunder."

From there, he immediately goes on to describe in long passages which I won't read, unless you prefer --

Q--No.

A--that this represented precisely the sort of concern the poet here represented in my mind and my interpretation of the challenging of the existing forms and structure in order to get to the essence of the spirit of the thing and it was this submission as we cited in "True Story" to something that was so real and so earthy, so real, a part of the personal existence to the will of God as he knew it.

He senses a mystical position. At point, he realizes through this gaze that the illumination of God was made apparent to him.

Q--I see. Thank you. Now, you have stated that there is a historical antecedent for the use of the graphic arts broadside, particularly in German. I believe you mentioned some Japanese school in this vein, also?

A--Yes.

--Is it true, also, that the same technique has been utilized in this Country in both magazines and posters and so forth that have appeared on the scene in the last ten years or so?

A--Yes. It has a much more respectable heritage than that.

We go all the way back to Thomas Paine or even to Benjamin Franklin, to notable characters in our history who made it a common practice to publish their thoughts on political experiences and and even into some sense their literary experience, in terms of the broad, single printed sheet that was distributed sometimes freely, sometimes at nominal cost.

To point those -- perhaps I should just add this particular byline -- that in the last ten or twelve years, I think your question implies a different attitude. I did mention a sort of renaissance of the concern with graphic arts and connected very much with poetry and with painting and with graphics in general, yes.

Q--I will not show you a poster that says "Fuck Communism" and I will ask you if you are familiar with this poster.

(The witness examined the poster,)

THE WITNESS: Yes, I am.

BY MR. McDANIEL:

Q--Is this poster for sale in this country?

A--Yes. It is for sale, and I believe it is advertised for sale, also, in the The Realist publication. I have seen it for sale in bookstores, too.

THE COURT: That is not a bumper strip, is it?

THE WITNESS: No, it is not.

THE COURT: Do you find many of those over at UCLA?

THE WITNESS: I haven't seen too many of them around. I suspect there are students who have them up in the rooms, yes.

THE COURT: And not at the gate. I see.

BY MR. McDANIEL:

Q--It might even appear on some professor's walls; isn't that correct?

A--I think that over at Valley State --

THE COURT: You can state the fifth Amendment.

THE WITNESS: No. I don't have to.

As a matter of fact, I do know a professor at Valley State College who was involved in some interesting discussions with this colleagues because he had that very poster -- not that one, but one just like it -- on the wall of his office at school. So, there was some concern about the intent there.

THE COURT: He made a protest? You mean the professor is protesting?

THE WITNESS: I think the real thrust of the protest was perhaps lost on those.

BY MR. McDANIEL:

Q--It might have been some Communist oriented people that didn't like this.