Victor Brauner

It is tempting to regard Victor Brauner, from the art historian's point of view, as a prototype for the impending freak-out revolution of the visual arts. He saw both his work and his own relationship to it in essentially psychedelic terms--well before Timothy Leary and Richard Alpert began their epochal researches into the effects of LSD. In 1961, for an exhibition of his paintings executed between 1939 and 1959, Victor Brauner wrote: "La recherche de la peinture actuelle ouvre un temps indéfini, élargi, englobant la vie secrète interiéure, agissant sur l'esprit." ["The search for present-day painting opens up an indefinite, extended time, encompassing the inner secret life, acting on the mind."] (1)

But it didn't really happen that way. However rich a source for the hip aesthetic and teeny-bopper vision of today the oeuvre of Victor Brauner may provide, neither the League for Spiritual Discovery nor other explorers of the realm within have yet focused upon the quietly mind-blowing phenomena created by this late, strange Roumanian-Parisian painter. They will, of course--for the same reasons that the German Expressionists, as artists, helped condition their contemporary critical and historical outlook, leading it to rediscover Vermeer and El Greco. In the same way the creative mentalities of the time among the Expressionists and the Cubists rediscovered the world of primitive art, as art (following the creative visions of Gauguin and Goethe, and in spite of a whole century of ethnology). It is just the groovy present that usually enables the gassy past to blast. Maybe this provides a sad, frustration-laden commentary upon the inefficient inertia and narrowness of taste in the so-called fine arts. For now we are beginning to take an intensely new, posthumous look at Victor Brauner's curious but consistent, personal but infinite, dark-light and magical world.

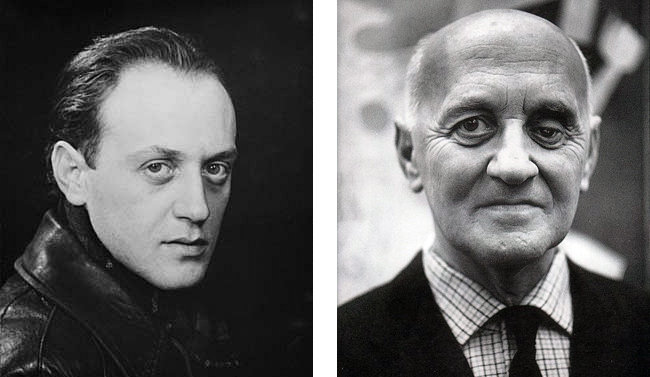

Left to right: Victor Brauner by Man Ray; Brauner in the 1960s

Saul Steinberg, as a fellow native Roumanian who also lived and worked in Paris, in some ways shared both the interior and the exterior worlds of his friend Victor Brauner. In a recent conversation, Steinberg (who is currently a Fellow of the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C., as their first Artist in Residence or, as he says, "Serenader of the Public Welfare") foresaw a new interest in Victor Brauner's mystical oils and subtly-hued encaustics, precisely because of the altered aesthetic stance engendered by the current hippie and teenage renaissance. This was further substantiated by Hedda Sterne, Steinberg's wife, who was also close to Victor Brauner in Paris. She felt that he would have loved today's youth, and also suggested that now perhaps (after it begins to realize some of the profound and pervasive implications of psychedelic phenomena) America may begin to open up more to Brauner's world of "interior space in its infinite grandeur."

This concern with the subconscious or preconscious life was, of course, no exclusive property. Nor is it a coincidence that a historical interest in the whole Surrealist movement should develop particularly in the last few years. Victor Brauner did exhibit with the Surrealists, from 1934 until 1949; Andre Breton and other Surrealists also wrote about his work. (2) After seeing a painting of his in the Salon des Surindépendents, Yves Tanguy met Brauner, and then introduced him to Breton. He was a "natural" Surrealist, whose archetypal images provided a perfect realization of Breton's theories. In fact, Brauner was a Surrealist even before Breton decided he was.

Left to right: Andre Breton, Yves Tanguy, Constantin Brancusi, Eugene Ionesco

Six years before coming to Paris, and ten before meeting Breton, Brauner showed his first paintings in Bucharest. There he also published an article entitled "Le Surrationalisme." This was in 1924, the same year in which the Manifeste du Surréalism appeared in Paris. No direct connections between the two events have been established, although it is sometimes forgotten that Bucharest hosted a lively, hip, intellectual scene at the time; it was strongly book-oriented, and any important or topical publication from Paris would appear (after an overnight train ride on the Orient Express) in Bucharest on the following day. Several other modern artists were nurtured in this vital climate, including Marcel Janco and Tristan Tzara, in addition to Constantin Brancusi two decades earlier. Brauner became a part of this literary scene in Bucharest, founding, together with the avant garde poet Ilarie Voronca, an ephemeral revue entitled 75 HP, in which he published his own manifestoes. He also announced himself as the inventor of "Pictopoésie." Rather than being merely another tired metaphor based on the Horatian dictum, "Ut pictura poesis," Brauner defined his new concept thus: "La Pictopoésie West pas de la Poésie. La Pictopoésie n'est pas de la Peinture. La Pictopoésie est de la Pictopoésie." ["Western Pictopoetry is not Poetry. Pictopoetry is not Painting. Pictopoetry is Pictopoetry."] (3)

After an earlier trip to Paris, Brauner decided to settle there in 1930, first developing friendships with his compatriots Brancusi and the philosopher Benjamin Fondane. Writers and poets, especially Eugene Ionesco, another Roumanian who wrote under the invented name Gherasim Luca, came to be among his closest of friends, although he certainly did not try to match their literary work, nor indeed later, that of Surrealists like Breton.

Brauner lived in a world of fantasy where the lines between his conscious and his subconscious were never clearly drawn. Significantly, perhaps, he rented the studio which had previously belonged to le Douanier, Henri Rousseau. He read a great deal in psychoanalysis; and according to Hedda Sterne, developed an intense interest in extra-sensory perception. This is all the more understandable when we read that his father was a passionate devotee of spiritualism, magnetism, and hypnotism, who was in correspondence with some of the mediums of the time. But there are in Brauner's own biography several curious anecdotes that relate to a clairvoyant quality. The best-known of these was recounted by Pierre Mabille in the review Minotaure, and concerns a work painted shortly after Brauner established himself in Paris, "Autoportrait" a l'oeil enuclee" (pictured at top of page).

Although he was never able to explain what prompted this self-image, the visual theme of a mutilated eye reappears in the following years. The film Un Chien Andalou made by Luis Bunuel and Salvador Dali in 1929 could be a general source, with the unforgettable slicing of an eye by a razor (image above). (4) What was not to be anticipated was the event some six years later when Brauner lost his left eye, the inadvertent target of a glass thrown by Oscar Dominguez during a party ruckus.

Some writers have seen another anticipation of this dramatic event in a painting with a tiger and the large letter "D," the initial of Dominguez. An even more peculiar premonition, however, occurred when Brauner first arrived in Paris. At Brancusi's suggestion--the older compatriot just wanted to see what facet of reality interested Brauner in his new environment--he took a series of photos of the street, and one shot in particular of the house, at that time totally unknown to him, in which the party was held where he lost his eye years later. Another time Brauner had a strange idea that he might lose a hand, and had actually purchased an artificial wooden hand. Fortunately, however, friends kept a close and careful watch to insure against any possible grisly accident.

Sarane Alexandrian has observed several stylistic biographical periods in Brauner's work, beginning most notably with "la periode des Chimeres" which starts in 1938, when he returned to Paris after a long stay back in Roumania, (5) and which is also called "la periode des crepuscules." Ten years later, after years of hiding out during the war--while most of his friends had been able to emigrate to America--Brauner finally split with Surrealism. This was an event as profound as the loss of the eye, according to Alexandrian, and marked the end of what had become a "periode hermetique." The inherent Surrealist aspects of his painting remain, even through a subsequent period of anguish, "la periode des Retractes," which was brought on by physical and material difficulties around 1951. But then the recognition (that had always seemed to just miss him before) finally began to come his way--particularly in Europe during the last ten years or so of his life, and somewhat more recently in the United States.

To understand Victor Brauner only in the context of Surrealism, however, is to risk overlooking one of the most important aspects of his work: the Hassidic touch, the humour and fervent joy together with the elegance and sophisticated wit. Brauner's pictorial language was always heavily autobiographical, and sometimes darkly mystical even during happy periods; in these ways it was still very much Surrealist, as his art was perhaps always. But Surrealism took itself so seriously, at least in public, that we might have difficulty finding among its traditions and manifestoes a convincing source for this other essential ingredient in Brauner's poetic visions and private mythologies.

Brauner's Hassidism was not literal, as he was not oriented toward established religion. Theologically his position would probably parallel those of the extreme Protestant in Christianity, of the inspired Sufis in Islam, of the radical Hassidim in Judaism, or of the innumerable individual Holy Men throughout India. But culturally and stylistically it was the Hassidic element in his native Roumanian background that forms the most important and immediate frame of reference for his art. Three main elements comprised the social and cultural structure of the Roumanian Jewish population: the native peasant stock, a constant influx of Sephardic Jews from the south, and (particularly following the Pogroms) a filtering down of Hassidic Jews from the north. It was this latter group, almost exclusively, that carried with it the sense of a subtle, sophisticated, eminently civilized tradition. The modern Hassidic movement was initiated, as Saul Steinberg has suggested, at the time of Louis XV, of Mozart, and of those distinguished, suave and worldly gentlemen who were responsible for the original idea of the United States of America--these men and their various courts certainly would have Understood the "telegraphic" mode of communication in Hassidic culture. A parallel in style might be found in the razor-honed drawingroom conversation of Oscar Wilde, and in George Bernard Shaw's happier dialogues. Speech and logic were conceived as delicate, sharp instruments for piercing through the obfuscating character of external reality; statements were intended to reveal the essence of an idea or situation in the most elegant and economical way possible. That this represents a remarkably high level of civilization is suggested by the similar moments in history when such an aesthetic has been possible, whether represented by the epigrams of Wilde, the Sufic poetry of Omar Khayyam and Hafiz, the one-page complete novels of Franz Kafka, or the tradition of the Zen ko-an.

Two important distinguishing features of Hassidism, although surely not its exclusive property, are the strong anti-literary bias, and the pervading note of humour and rejoicing. The 18th century founder of modern Hassidism, BaalShem-Tov, held that man was nearest to God when he was rejoicing, and that the prayers of the unlettered were as valid to God as those of the Talmudists, so long as they were prayers of joy. The special Hassidic emphasis upon good food and music with dancing as a potential means for personal, mystical communion with the Deity, seemed to appeal to Victor Brauner very strongly, together with its originally non-sectarian stance. There are still the dark sides to Brauner's art; but they have already received critical attention largely because of their close relationships with Surrealism. It is the other happy aspect, documented by Brauner's "Pictopoems" of the pleasure principle, that has not received appropriate concern.

"L'Aeroplapa"

There are friends of Victor Brauner who remember his first success in Paris, and his response, which was to immediately squander the money in buying food and paying for music for all his friends. His subsequent successes were followed by further parties. Even the cultish Surrealists were to be enlivened by festivities. At the same time, Brauner was definitely not a gregarious "homme de parade" like Dali or Picasso--rather he remained silent, enigmatic, and often isolated for long periods of time. Even his humour is "noire" more often than not. Such dramatic contradictions, even polarities, are represented by one of the recurrent symbols in Brauner's painting: the wand with an image of the sun at one end and the moon at the other.

It appears in an important painting, "Les Amoureux, messagers du nombre" (1947, shown above), the curious work with two figures from the Tarot deck, and with an inscription on the back that prefigured an eruption of Mt. Etna, pictured on the front side as the headpiece of "le Bateleur." In a lighter context it also appears in "L'Aeroplapa" (1965) (pictured above). This is one of those extraordinary later pieces painted on canvas, but set in such witty and outlandish frames, of polychromed wood, that the works really deserve to be considered as much wall sculptures as paintings.

"La Mere des Mythes"

It is in the titles of these later paintings that Brauner exemplifies the spirit of Hassidism as much as in the works themselves: the disarming iconic image of "L'Orgospoutnik," the funny and compelling "L'Automamma," with its archetypal implications involving the maternal surrogates of the television set and the automobile, and the deeply comic "La Mere des Mythes" (all of which were painted in 1965). Two formal elements that characterize all of Brauner's earlier work persist here: the exquisite relationship between Brauner as a draughtsman and Brauner as a colorist. The former quality relates his work to that of Steinberg, particularly in Brauner's painting with reflections of the Hassidic strain. Hints of this can also be perceived throughout Steinberg's oeuvre: in the humour that is so hard to pin down and in the high seriousness that eventually emerges. A good example is "Il Gabinetto del Proprio Niente" (1966), with its elegantly inventive and orderly cosmic statement. The other artist with whom Brauner has such strong affinities is of course Paul Klee. In their draughtsmanship, Klee is formally more inventive, Brauner more consistent in style. It is in the superb sense of color that they are most like each other, juxtaposing at times the most subtly daring hues. But the approach of Klee to color, as well as to drawing, is radically different from that of Brauner. Klee was methodical and scientific, however inspired; and Brauner was, on top of his talent, driven almost by intuition and inspiration alone.

One of Victor Brauner's most remarkable pieces among the late works is a painted sculpture entitled "Bel Animal Moderne" (pictured above). Here he is very close to Steinberg's wit, and to Klee's images, such as "The Mask of Fear," and the "The Mocker Mocked." Brauner's animal is, of course, distinctly human, in a Chaplinesque combination of humour and helplessness. This is the way some of us, in kinder moments, are tempted to see the members of today's teeny-bopper and hippie revolutions. And, because love and kindness and joy are as much a real, integral part of those revolutions as is a revised attitude toward violence, it may also be the way in which many heads and swingers see us.

Victor Brauner was one of those artists able to create from his own internal point of reference, incisive, accurate symbols that may have come to stand as new archetypes of existence. As he once wrote about this whole process, "J'ai vu mon image cosmique, voyageant en moi-même, bercée lentement, voluptueusement dans sa profonde inmensité intérieure." ["I saw my cosmic image, traveling in myself, cradled slowly, voluptuously in its deep inner immensity."] (6) Perhaps the revolution of youth with its new media, intermedia, and multimedia for artistic "manifestations," the acid scene, the psychedelic poster art and the new weird rock and roll, is merely linking up with directions already magnificently indicated by our twentieth century artists of interior space like Victor Brauner. For as his friend and compatriot Eugene Ionesco wrote, "... what a wealth of space there is within us. Who dares to adventure there? We need explorers, discoverers of unknown worlds, which lie within us and are waiting to be discovered." (7)

NOTES

1. Victor Brauner, preface to the catalogue for the exhibition "Victor Brauner Dipinti 1939-1959." Rome, Galerie l'Attico, 1961. The most recent exhibition of Brauner's painting was at the Alexander Iolas Gallery in New York, March 1967.

2. Andre, Breton, Le Surréalisme et la peinture. New York. Brentano, 1945.

3. Alain Jouffroy, Brauner. Paris, Le Musée de Poche, 1959, p. 23.

4. For a treatment of this theme see Gerald Eager, "The Missing and the Mutilated Eye in Contemporary Art," Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, VOL 20, No. 1, Fall 1961. Another possible source, not mentioned by Eager, however, is the old woman's broken glasses and mutilated eye in the great steps of Odessa sequence of Sergei Eisenstein's film Potemkin, 1925.

5. Victor Brauner: L'Illuminateur, Paris, Editions Cahiers d'Art, 1954, p. 39. See also by the same author, "Victor Brauner," L'Oeil, No. 101, May 1963. I am grateful to the Alexander bolas Gallery for making these and other publications on Victor Brauner available to me.

6. Preface to the catalogue, "Victor Brauner Dipinti 1939-1959," Rome, Galerie l'Attico, 1961.

7. Eugene Ionesco, Notes and Counter Notes: Writings on the Theatre, New York, Grove Press, p. 231. I am particularly grateful to Simone Swan for her help in preparing this article.